Forespar's Point of View

Blogging About Life on the Water

Steering in Big Waves

What’s a big wave? Is it the 100-foot wave from The Perfect Storm”? Could it be the waves from a TV show called Bering Sea Gold, when they tell us there’s a storm, and it looks like all of 12 knots of breeze and two-foot chop?

The answer is yes. Any wave that makes you feel that you and your boat are in danger is a big wave. All that matters is that the waves are challenging you, and you’re nervous about handling them safely. There are some basic rules that can help:

- First -If conditions scare you, don’t go out. Getting macho can get you and your passengers in deep trouble. Getting back on Monday morning isn’t worth risking the safety and sanity of your crew.

The classic example is the trip back home from Catalina Island. You left the mainland early on Saturday, and it was flat with no wind, so you zoomed over (zoom speed is relative – maybe six knots from the Yanmar in the sailboat, and 25 knots from the twin Volvos in the cruiser). You leave for home on Sunday afternoon, and there 32 knots of breeze pushing some healthy wind waves along with a big swell rolling down the channel, and you’ve got 26 to 45 miles to go with that on your beam or under your quarter.

You are relatively inexperienced, but you’ll probably make it. You’ll beat up the boat, and scare the pants off your crew and yourself in the process. The crew may never get on the boat again. Or, you are experienced, and you’ll make it. You’ll wear yourself and the crew out, and the boat won’t be real happy either.

- Second- There’s no better teacher than experience, but try to gain that experience with an old hand aboard to help you learn. Often the difference between the emotion “We’re gonna die” and the comment “That was a big one” is usually perception and a twitch on the helm.

If you are next to the helm on one of those days, and the driver is calm and under control, it’s amazing how much you can learn just watching and listening. Then when you trade places and you’ve got the helm, have a calm voice in your ear, coupled with the positive results, can help you learn a lot, and apply it at the same time. Then you gain the confidence to try it yourself.

- Third – Practice. When you go out, and it’s lumpy, take some time to drive the boat both uphill (into the wind and waves) and downhill (away from the wind and waves). Learn what makes the boat feel and respond best under current conditions. You check the weather, then look out the harbor entrance. If you see other boats of your type in the vicinity, go out and play. Practice going into the wind, downwind, into the waves and away from them.

Going into the waves, while often scarier, is easier on the boat and the driver when you do it right.

Don’t worry about your specific destination – as long as you’re making up distance to the mark (technically VMG – Velocity Made Good), you’re doing well. If you steer at an angle somewhere between 20 ⁰ and 45⁰ off the face of the wave, the boat is a lot more comfortable, and is actually faster than heading straight into the sea. You don’t get the big flying spray, and you don’t get the big pounding crash, either. And, you’ll be under control.

Not steering at your mark seems counter-intuitive, but any racing sailor can tell you that it works.

That’s nice, you’re thinking, but at some point I have to make up for that angle away from the harbor mouth. You’re right. You do. If you’re paying attention, you’ll find a periodic flatter spot between waves that will allow you to make the turn (tack) without wrestling the boat over a bigger wave.

Heading downhill requires more touch, and more attention to your helm. The basic design of most powerboat hulls has a broad, usually flat, surface for the following wave to push on, along with a more or less square corner (the quarter). This means that when that big wave comes at the stern, it lifts the stern while pushing on that flat surface. The combination of shapes and forces make the stern want to go to the side, and the boat wanting to turn parallel to the wave’s face, tilting away from the rising wave. This can make for some interesting or even dangerous moments. Sailboats do the same, but with a less exaggerated motion.

With some practice, you can learn to anticipate your boat’s tendencies, and start steering up the face and down the backs of oncoming waves, into the direction that swinging stern takes (It’s called “Yaw”) on following seas.

- Fourth – Watch Your Speed. If you pay close attention to your boat speed relative to the waves, and adjust accordingly, you’ll find the sweet spot. Wind waves are usually moving at speeds from 13 to 18 knots, so you want to work around that basic datum. If you’re steering into the waves, and in a hurry with 15 knots of boat speed, you’re meeting big walls of water at 30 knots (just under 35 mph). The air is getting under your hull, and you’re flying a bit. That is a lot of energy your boat has to absorb when you hit the next wave. Saves a lot of wear and tear on the boat and the bodies aboard.

- Fifth – Steer easy. Remember, the rudder is turning the stern, not the bow, so you’re always just a beat ahead of the boat’s motion. That means you can be making exaggerated corrections, larger and larger turns, out of synch with the waves. That leads to more bounce, more roll, and frayed nerves. Usually, it’s just slow the boat speed a bit, slow the steering a bit, and get into the rhythm.

When steering off the wind, some of the math works for you. If the waves are moving at 13 knots, and you throttle back to about 13 knots, keeping the bow down enough to increase your waterline (hence control and comfort), you’ll find that steering the boat and managing the course is a great deal easier. The waves are coming at you a lot slower, and you have much more time to make your adjustments to steer a comfortable and productive course. With some practice, you’ll find yourself actually surfing the boat on the swell.

Take it easy. Think safe, learn well, practice and just slow down. Your boat, your back and your crew will be much happier.

Hunt Made Us Go Faster

C. Raymond Hunt  had one of the most significant impacts on modern boating, right up there with Ole Evinrude and Olin Stephens.

had one of the most significant impacts on modern boating, right up there with Ole Evinrude and Olin Stephens.

Hunt was the naval architect credited with designing the first deep-vee hull(s). He started working with sailboat and lobster boat designs in the 1930’s in Massachusetts, and experimenting with deeper deadrise hulls for powerboats in the 40’s. That led to the revolution in powerboats, with deep-vee designs creating boats that knife through the water rather than sliding over it, with faster smoother and much more seaworthy rides, especially offshore. In 1960, Hunt designed and Bertram built Moppie, a 31-foot boat based on a tender Hunt made himself, and used to win the famous Miami to Nassau Race. That became the Bertram 31, a version of which is still in production.

And, it wasn’t just Bertram. Hunt designed the original 13-foot Boston Whaler. in 1957. C. Raymond Hunt & Associates designed and engineered small boats, big boats, racers and trawlers for many builders, including Chris-Craft, Grady-White, Grand Banks and more than a few others.

So, next time you’re powering along offshore, thank Raymond Hunt. He’s why your boat is fast, smooth and stable.

Inventing the Outboard

Summer of 1905-ish, Ole and Mrs. Evinrude were picnicking on Lake Okauchee in Wisconsin.

Ole was sent for ice cream, and he rowed to shore, and bought the ice cream. By the time he got back to the family, the dessert had melted. Ole, the machinist and combustion-engine tinkerer, was a bit irritated. In 1907, he came up with a 1.5 horse transom-mounted gasoline powered outboard motor.

In 1911, he patented his invention, and in 1913 sold his interest to his partner in the Evinrude Motor Corporation. After five years off, he introduced a 3 hp aluminum model that weighed 48 pounds. He then joined forces in 1929 with his old company and Johnson Motor Company, and created the small boat revolution.

In 1911, he patented his invention, and in 1913 sold his interest to his partner in the Evinrude Motor Corporation. After five years off, he introduced a 3 hp aluminum model that weighed 48 pounds. He then joined forces in 1929 with his old company and Johnson Motor Company, and created the small boat revolution.

You can still buy a two-cylinder Evinrude – or one with up to 300 horsepower.

Six Timeless Seamanship Lessons

Beginning in the 50’s, BOATING magazine featured seamanship advice articles, many of which are applicable and basic today. Here is sampler

Have a Plan B

From January 1958: Unless you know firsthand that all your passengers are skilled at boating, assume they know nothing of what goes on between the gunwales. Robberson suggests that you assign each crew member a different task, giving each a role to play on board. Have one handle cushions and life jackets, for example, another to help with the dock lines, and another to help with engines and helm . That way, everyone has a specific task when you need help. From the time they board the boat, you can get them interested in doing things, and they’ll not only be better company and enjoy the ride more, but they’ll be good for something in an emergency.

Lights

From 1960: In daylight objects around you are usually easy to identify. They are big or small, short or tall, round or square, and they are plain to see as bridges, docks, land, beacons, buoys, or boats of various kinds and sizes heading one way or the other. But, at night, all the familiar shapes disappear, and all that’s left are various and sundry points of light: Some white, some green, some red, some orange, some blinking, some constant, some stacked, some horizontal, some moving, some still. If you can’t read these, lights, you should be ashore, preferable at home, learning navigation lights. The alternative can be bad.

Anchors “Away”

From 1977: Ellen Matthew wants you to think about scope – the length of anchor rode you have out under various conditions. With a short scope, the holding of even the best and heaviest anchor is reduced, because the high angle of the rode tends to pull the anchor up instead of along the bottom, breaking it loose. Coast Guard and Navy tests show that a scope of 7 to 1 is right for average conditions (in 10 feet of water, you want 70 feet of rode), at least 5 to 1 for ideal conditions (a calm lake or currentless harbor), and at least 10 to 1 during a blow.

Do No Harm

From 1983: Right of Way – Don’t hit any or anything, and don’t get hit. People often forget that boats don’t have brakes. So, simply put, the more maneuverable vessel stays out of the way of the less maneuverable. Sailboats watch out for rowboats, powerboats watch out for sailboats, and we all watch out for work boats. Like wise, our smaller craft are supposed to give way to ships, especially in tight quarters, because we can get out of their way easier than they can get out of ours. Know the rules and regulations, but be ready to dodge when boats meet. Remember the Law of Tonnage – if they’re bigger than you, being right may not be worth it.

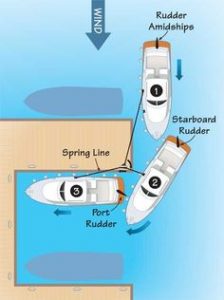

Spring Line Docking

From 1998: Sailboats go bow in. Powerboats back in. We have a tradition to uphold. And remember sneaky trick #110. When the wind and/or the current are stacked against you, use the spring line method. Lay the boat along the pilings at the end of the dock, or along the end of the dock itself, with the stern (or bow) protruding into the slip. Wrap the line around the midships cleat and then loop around the cleat on the dock, or the piling. Turn the wheel toward the dock, and set the line tight until the bow (or stern) begins to work around, and then ease off as the end of the boat swings into the slip – and you’re home free.

There’s the old saying about docking. “Go slow like a pro, or fast like an ass”. Slow and steady gets you in with no damage – boat or brain.

Anchoring Etiquette

Boaters usual ly know that anchoring in the channel or the fairway is not only a bad idea, but illegal. and unsafe.

ly know that anchoring in the channel or the fairway is not only a bad idea, but illegal. and unsafe.

Most of the time, it’s not that simple. How’s your anchoring etiquette?

The First Boat In Sets The Rule

You motor around the point into your favorite cove, and you see another boat already anchored, swinging off a single hook. Etiquette dictates that you do the same, dropping your single hook on a spot that will keep you clear of the other boat when wind and tide change. If it’s relatively shallow, some of us even buoy the anchor, so others will know where it is (a spare fender and a few feet of paracord will usually do).

Then, how do you compute the swing radius – yours and the other boat’s? You can always do the math of a right triangle using water depth and scope to get the unknown – the distance from the boat to the anchor, But, assumptions of a 7:1 scope aside, that swing radius is going to change. Tides rise and fall, wind and currents change, and different boats react differently to those changes.

Keel sailboats react faster to current shifts, and later to wind, while power cruisers, especially those with two or three deck levels, react to wind faster than current. To make it even more fun, boats using all-chain rodes usually lay to scope of 3:1, as opposed to the 7:1 typical of boats with a rope rode. And funner yet, the other skipper may have more rode out than you thought, and you’ve swung to lie right above his hook, of course just when he/she is trying to leave – no big deal, unless you’re not on your boat and didn’t leave an anchor watch.

You Set the Rule

You come around the point to the “hot spot” on a summer Saturday and you’re the first to arrive. When that happens, the basic rule is to set two anchors – bow and stern – which allows more boats to enjoy the day. After you’ve set the two hooks, you can call “first in”, and there’ll be the usual shouting when the fleet arrives, but you’ll be there, and in good shape.

Don’t Be In A Hurry to Get Off

As tempting as it may be, don’t jump into the dinghy with your picnic or clamming basket in hand. Take the time to be sure you’re not dragging the hook. Take a couple of “ranges”, by lining up two stationary object ashore – in two or more directions – a couple of trees, rocks, etc. Wait a while, and if they stay in line, you are secure. Then go where you must go. Leaving crew on “anchor watch” to deal with emergencies is a good plan if you’re going to out of sight of the boat.

Now you’re a good anchor neighbor. Etiquette means good manners, and good manners make friends.

Never Assume They Can See You…

I know it’s not sailing, but the lesson is clear. These folks were salmon fishing on the Columbia River, and saw the boat coming at them. After the usual waving and yelling, they took appropriate action and dove into the cold water. The cruiser driver was sitting down driving, and couldn’t see the fishing craft over the dashboard and bow. You can see why.

Anything With a Swim Step

It’s 2 a.m. You’re on a mooring in your favorite getaway harbor. The party on the boat three cans down has finally died away. And, you still can’t sleep. Something’s missing. You jump up and dash topside, flashlight in hand, looking over the side and around the anchorage. The dinghy got away! It’s not banging on the side at the end of the painter! That’s what’s missing….

You glance over the transom, and there she is, firmly clipped to the swim step. Not swinging, not banging on the side, not trying to escape. Easy to board, easy to release, and easy to attach and exit. That’s a side benefit of the Forespar Quik Davit.

We added the Quik Davit to the swimstep of our Grand Banks so we’d have an easy way to hoist in the dinghy when moving to a new spot, rather than use the the topside power hoist, etc. It works perfectly as the name implies, and as our private, mobile dinghy dock.

Friends use the Quik Davit on a variety of smaller and larger power boats as the primary davit because it’s easier to inflate the dinghy at the home dock, hoist/tilt it onto the step, and drive away – and reverse the process when back at the home dock. Sailboat owners do the same, usually for shorter cruises, and for the above-mentioned reason.

Check Quik Davit out. It installs easily on both the dinghy and the step of just about any boat, is easy to use, the price is right – And you’ll sleep better.

A Really Bad Day

So you think you had a bad day….A post hurricane mess from Cudjoe Key. This among the many, many horror shows coming in the wake of Irma. We can hope no one was home, either ashore or afloat.

Charlene Norris Joins Us

We are pleased to announce that Charlene Norris has joined the Forespar Sales Team as our Customer Service and Sales Assistant for the Company, beginning October 2017. Her role is to assist with OEM orders and issues, become the liaison between the department and Field Sales Representatives, and to help with the overall administrative operations with the Sales and Customer Service areas.

For Our Sales team members in the field, Charlene’s primary goal is to answer questions, meet the needs of and make life easier and better for you and for our customers. Sales and purchase orders will continue to be processed in the normal way with Linda and Randy on the Sales Desk. If you have any additional administrative needs for yourself or for your customers, let Charlene know.

Charlene has a broad background and comes to us with more than 30 years of administrative and customer service experience in a variety of industries. She is technologically savvy and understands the importance of communication within the team and with Field Sales Representatives, the Sales Department, and our Customers. Charlene’s modus operandi is “See it through to the end, no matter what obstacles may come my way.”

Many of you may already know Charlene, as she has been working closely with Bill Hanna, David Levesque, and Randy Risvold for several months. Going forward, if you have questions about New Customer Setups, Service Issues, Information Requests, Literature & Sample Requests, Show Support, Account History, YTD/PYTD Sales Numbers, Sales Trends, Outstanding Invoices, Commissions and all follow-up, please contact Charlene at: 949.858.8820 ext: 107 or email: CharleneN@forespar.com.